Using the Archive of a ‘great man’ to learn about ordinary people

- The danger of making assumptions about the Churchill Archive

- Using the Churchill Archive to investigate ordinary lives

- Searching further

The danger of making assumptions about the Churchill Archive

Here are just a few randomly chosen sources from the Churchill Archive. They remind us that Churchill was a very high-profile political figure for much of his life.

The Archive is also extraordinary in the amount of personal material it includes. Often archives only show the public life of an individual but the Churchill Archive is full of information about Churchill the man – and child – that many students can identify with.

Of course, when we see sources like this there’s a great danger of assuming that the archive contains only material about Churchill, or about Churchill and his fellow politicians and leaders. This is understandable, given that many of the documents in the archive are like these.

A telegram from US President Roosevelt to Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1944. The telegram is telling Churchill about increased tank production to help the British in the War and is part of our investigation on the ‘special relationship’ between the US and the UK. See the full document in the Archive here.

In this letter, Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph, complains in a letter to his nineteen-year-old son about Churchill’s ‘misuse’ of a valuable watch, comparing him to his brother who, he says, is ‘vastly ...superior’ to him. See the full document in the Archive here.

Using the Churchill Archive to investigate ordinary lives

In reality, the Churchill Archive contains much more than papers relating to Churchill’s family and career and the history student who’s interested in trying to discover more about ordinary people and their views and experiences can find much in the Archive.

The key lies in one particular skill of the historian – the ability to make inferences. In simple terms many, perhaps even all, historical sources usually reveal something to the historian which they didn’t originally intend. This doesn’t mean that the historian is looking for secret codes or even subtle propaganda. Most documents say something about a particular subject. However, in the process they usually reveal something about the author. They may of course tell us about how people thought of Churchill but usually the documents will reveal more than this. They may reveal something about the society in which the author lived, particularly the values, assumptions, concerns, fears or hopes of individuals and of the society to which individuals belonged. It can also reveal something about the relationships between politicians or government and the people they rule.

Here are some examples.

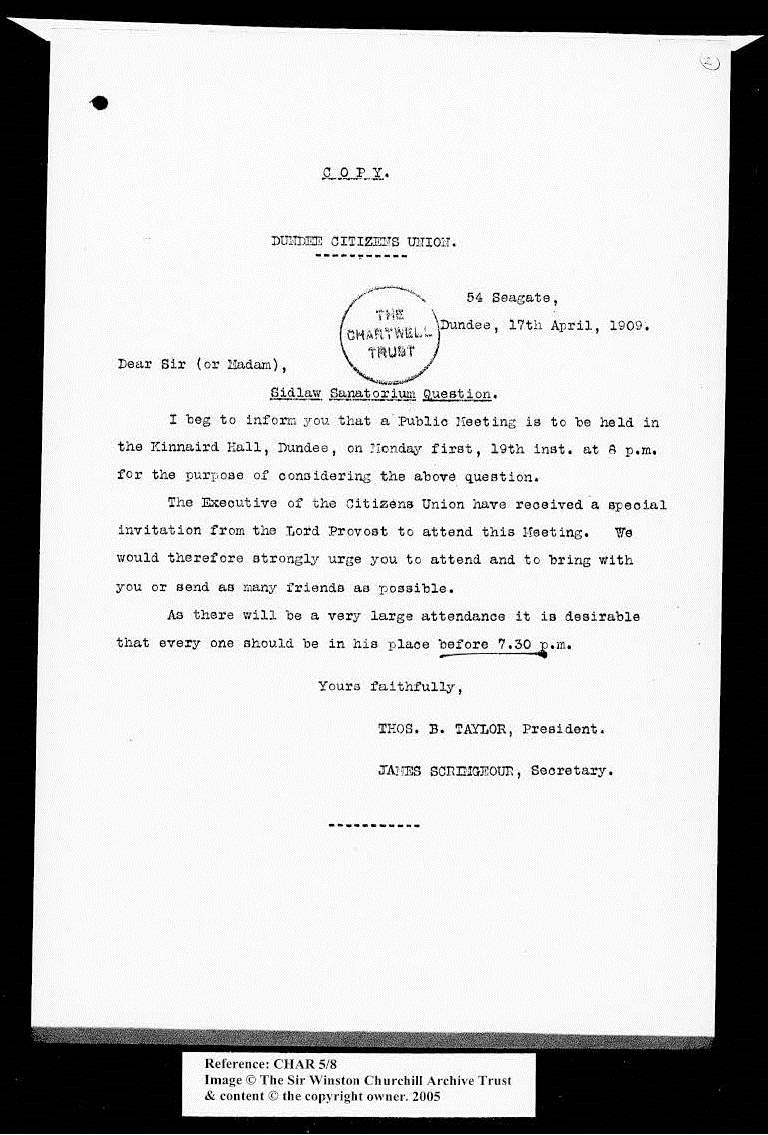

See the full document in the Archive here.

This document is a letter to Churchill inviting him, as the local MP, to a meeting about the need for a new sanatorium (a hospital) in Dundee in 1909. At the obvious level it tells us that Churchill was invited to the meeting. However, when we think more deeply we can see that in this area at least there was obviously concern about health care. The source also shows us that there were some citizens at least who were taking action on the issue and mobilising themselves and others. Is this a case of the citizens wanting the state to take over more aspects of life or is it a case of active citizenship? Was this a one-off case or were more regions expressing concerns on this issue?

This is a proposition which could be tested by searching the archive and by other relevant links such as this.

You can also find a fascinating collection of source material on social reform in our investigation here.

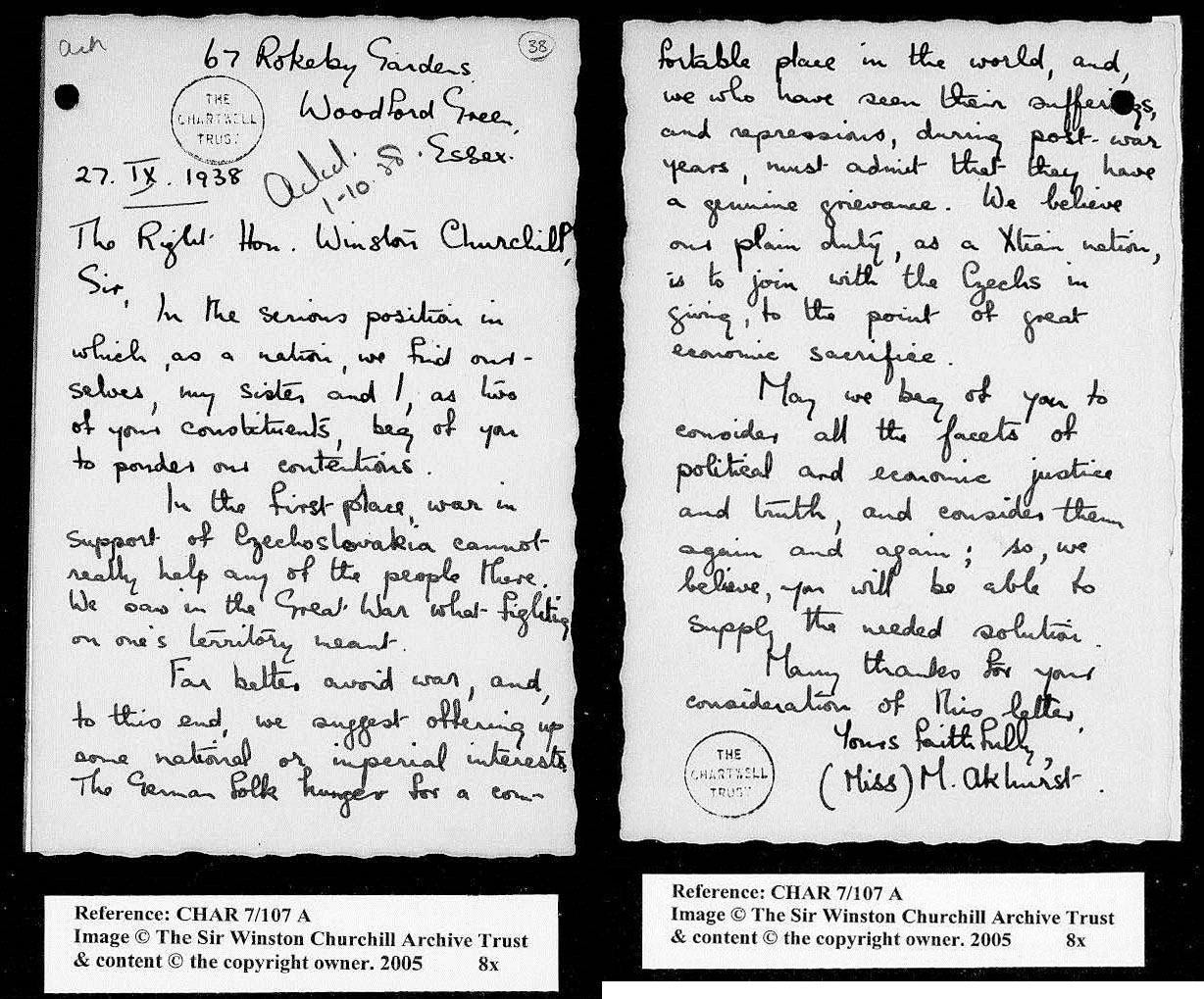

See the full documents in the Archive here.

This document is from a different era and on a different topic. At the simplest level, it tells us what Mis Askhurst thought of the current international situation. And this is a critical point. This letter doesn’t really inform us about the international situation in any great detail. It doesn’t even reveal much about Churchill’s stance on the British government’s policy of appeasement in the 1930s. What it does reveal is the anxiety of a British citizen about the international situation. This is useful in its own right, but the Churchill Archive allows us to test the hypothesis that Miss Askhurst was unusual in being interested and or unusual in the views she held. This is the underpinning theme of our investigation on Appeasement.

And if students or teachers want to pursue the issue in greater depth, the Churchill Archive allows them to work through far more of the letters sent to Churchill and to try to make an assessment of how far some of the ordinary population of Britain felt about appeasement.

Searching further

The examples we’ve looked at here are part of the Churchill Archive for Schools resource. All of the material is structured in such a way as to help students develop their powers of inference. However, teachers and students might want to explore the collection further and search on other areas on which the Churchill Archive may be able to shed light.

Some suggested searches are:

- Living conditions

- Health

- Levels of literacy

- Science

- Technology

- Trade and the economy

A simple word search is a useful way to begin a search on these or other areas, but there’s some very helpful guidance on refining and improving search techniques in our guide ‘Ask the Archivist – or ‘How do I use the Churchill Archive?’

Good luck!